How good would you say your church is? Not, “How good are your programs?” or “How good is your preaching?” I mean: “Is your church good?” in the way that God is good (Psalm 25:8), the original uncorrupted creation is good (Genesis 1:31), and the gospel is good news (Mark 1:1). This (intentionally cheeky) question exposes the way that many of us probably think of ministry success. We measure our ministry’s success by the number of participants, the satisfaction of our members, or the effectiveness of our programs. We may even measure our ministry by the laudable (and biblical) things we do, such as the number of baptisms, the precision of our theology, the involvement of members, or the ministry’s positive influence in the community.

But in Scot McKnight and Laura Barringer’s A Church Called Tov: Forming a Goodness Culture That Resists Abuses of Power and Promotes Healing, ministry leaders are challenged to consider whether they are calling their ministries to goodness, as defined by the cruciform example of Christ. The Hebrew word tov is usually translated as “good” or “pleasing” in the Old Testament. In A Church Called Tov, goodness is primarily a quality of culture and character, rather than a static attribute. It’s a feature of faithfulness, a fruit of the Spirit, rather than a measure of “impact” or even “effectiveness.”

In the trenches of ministry, so many concerns rise to the level of primacy: Will giving meet the budget this year? How can we get members more involved? Do we have lessons prepared for this Sunday’s children’s ministry? While all these questions are certainly vital to the good working order of a ministry, there is an even more fundamental question that we must regularly attend to as we lead our ministries: As an organization, are we forming people towards goodness or evil? Towards greater health or toxicity? Christlike self-sacrifice or Satanic self-centeredness?

Forming a Toxic Culture

What do we mean when we talk about church culture? The culture of any group of people describes the “unwritten rules” or assumptions within that group. It can be seen in the sensibilities or instincts of the members of the group, or it may be seen through the interactions and relationships formed in the organization. It may be expressed and reinforced through doctrinal or value statements, policies and procedures, or ministry affiliations. But most fundamentally, an organizational culture is known by its fruit. Jesus told us, “Every healthy tree bears good fruit, but the diseased tree bears bad fruit. A healthy tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a diseased tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Thus you will recognize them by their fruits” (Matthew 7:17-20).

Culture is the fruit-at-scale of an organization. It is perpetuated by both church leaders and the congregation. McKnight and Barringer write, “Your church is its culture, and that culture is your church. Never underestimate the power of culture… A rooted culture is almost irresistible. If the reinforcing culture is toxic, it becomes systematically corrupted and corrupts the people within it. Like racism, sexism, political ideologies, and success-at-all-costs businesses, a corrupted culture drags everyone down with it” (16-17).

Unfortunately, there are many examples of churches and organizations (here, here, here, and here) that appeared to have ministry success, but it turned out to be a facade covering up systems of intimidation and abuse. Toxic cultures can be formed in organizations of any denomination, governance style, theological commitment, or mission emphasis. The only way to recognize a toxic culture is to open the organization up to a fearless moral inventory, trusting that God will honor faithfulness and transparency.

Forming a Goodness Culture

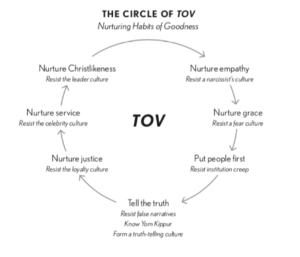

Goodness starts with the character of a ministry’s leaders. As they speak and act in ways that reflect God’s values, a culture of goodness will be formed. You can measure an organization’s goodness in a variety of ways (the authors offer seven different practices of organizations that can be described as tov, in the graphic at the bottom of this article), but one of the easiest ways to ascertain goodness is by asking how the organization responds to abuse.

Most Protestant churchgoers (82%) think that their church would correctly address a case of sexual misconduct in their church, even if it was costly to the organization. And yet, 1 in 8 Protestant pastors said a church staff member had sexually harassed a member of the congregation at some point in the church’s history. How many of those churches have reported the abuse to police? How many of them have sought to bring the harasser to justice? How many of them have led their churches to repentance, and provided the means for healing and restoration for the victim? Admittedly, we can’t know the answers to these questions. But we can think of many well-known examples of the mishandling of abuse (here, here, and 700+ victims here) and only a handful of examples of an organization taking responsibility for the abuse that occurred within their ministry (here).

In order to handle abuse and misconduct well, a ministry must have a deep culture of goodness based on God’s character and promises. These cultures are not formed overnight, but come as a result of years of small acts of faithfulness and self-sacrifice. Andy Crouch writes in Culture Making, “No matter how complex and extensive the cultural system you may consider, the only way it will be changed is by an absolutely small group of people who innovate and create a new cultural good” (cited in A Church Called Tov, 82). If you want your organization to reflect the goodness of God, it starts with a ruthless approach to character formation in its leaders. Character breeds culture. This is why Paul demands such high character qualities from church overseers in his letters to Timothy (ch. 3) and Titus (ch. 1). These overseers will see their role as stewards and managers who will one day be accountable before God. The ministry does not “belong to them,” nor does it exist to preserve itself or its own reputation.

What Are Ministries Good For?

The goodness of Christian ministries matters, because they represent God’s character and values to the world. It doesn’t just matter what ministries do; it matters how they operate. Many of us are probably familiar with 1 Timothy 3:14-16, which calls the church “the pillar and buttress of the truth” (ESV). However, notice what comes before. Paul writes, “I am writing these things to you so that, if I delay, you may know how one ought to behave in the household of God, which is the church of the living God, a pillar and buttress of the truth” (ESV). For Paul, the church’s behavior attests to the truth of its message. Without it, why should anyone believe what we have to say?

Churches and Christian ministries exist in order to show the world what our God is really like. He is holy and wholly loving. He is merciful and slow to anger, but he also demands that we, his people, tell the truth and care for the vulnerable. He commands shepherds to guard the flock that has been entrusted to them, which means taking reasonable measures to protect them from harm, physical and spiritual.

Good churches put a premium on grace and empathy. They encourage real repentance, even from their leaders. McKnight and Barringer write, “Pastors, by definition, pastor from their own personal Christoformity [being formed in Christ-likeness]. No pastor is perfect, that’s for sure, but pastors are to be mature enough Christians to be able to mentor others into Christlikeness as they are moving into Christlikeness themselves” (212).

Good cultures have solid policies that prevent abuse and encourage transparency from their leaders. They make a plan ahead of time to do what it takes to protect those in their care. They ensure that they are properly screening and training all those who work with the vulnerable, and they require Christlike character in order to serve in their ministries.

Good organizational cultures encourage honest and open communication among their members. When criticism or accusations come, leaders humbly listen, assess the allegation, and make a plan for a faithful response.

Why Do You Call Me Good?

This call to goodness is certainly a high calling for any Christian leader, but doesn’t faithfulness require goodness? In order to attain this standard, we must ask some difficult questions and be ready to hear honest answers. Here are some example assessment questions that ministry leaders should ask of themselves and their organization.

The closer you are to the “inside” of an organization, the harder it is to achieve objectivity. Consider asking these questions to people at different degrees of “closeness” to the organizational center (board members, management-level staff, lower-level staff, volunteers, parents, and outside consultants, etc.) for best results.

Are board members able to call each other out on sin and misconduct?

If any leader is in unrepentant sin, are there protocols for confrontation, discipline and/or removal?

Do you have protocols in place for staff members to report abuse to a disinterested third party who will respond with justice and compassion?

Do you have protocols for reporting Code of Conduct or policy infractions by staff members or volunteers?

Do you regularly talk about specific sin? Do you regularly encourage repentance for specific sin? Do you encourage grace and forgiveness?

Do you actively encourage truth-telling, even at the expense of the organization or influential individuals?

Do you have written policies or documents that reflect Biblical responses to sin?

Is a call to Biblical justice and righteousness a part of your discipleship model?

Below, you’ll find the “Seven Habits of Tov Cultures,” from McKnight and Barringer’s book. Here is a link to the book’s website, which includes discussion questions and additional resources for those who want to dig deeper or do a book study with other leaders.